Microsoft US Sovereign Cloud Myth Busters – CUI Effectively Requires Data Sovereignty

This article is contributed. See the original author and article here.

This article is the fourth of a series in the Microsoft Tech Community Public Sector Blog that explores myths of deploying Microsoft Cloud Services into the *US Sovereign Cloud with Azure Government and Microsoft 365 Government (GCC High).

We will focus on the myth that Controlled Unclassified Information (CUI) does not require data sovereignty. This article is written through the lens of requirements to protect CUI in the context of the U.S. Department of Defense for national security, such as in alignment with the Defense Industrial Base (DIB) and the Cybersecurity Maturity Model Certification (CMMC).

Executive Summary

Microsoft has prescribed the *US Sovereign Cloud with Azure Government and Microsoft 365 Government (GCC High) to protect Controlled Unclassified Information (CUI) and Covered Defense Information (CDI) consistently. Our rationale is that CUI includes International Traffic in Arms Regulation (ITAR) regulated data, and the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) requires Defense Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement clause 252.204-7012 (DFARS 7012) to protect it. We only accommodate that contractually across Azure, Office 365, and Dynamics 365 in the US Sovereign Cloud, built in a fully isolated environment that is both physically and logically separated. All services in the US Sovereign Cloud are contained within an accreditation boundary supporting US Export Controls requiring screened US persons and data sovereignty in the Continental United States (CONUS).

*For more information on the US Sovereign Cloud, please refer to the Understanding Compliance Between Microsoft 365 Commercial, GCC, GCC-High and DoD Offerings

Preface

If only I had a quarter for every time I’ve had to explain why we have a “Maybe” for CUI and CDI in clouds other than the US Sovereign Cloud.

Our mantra is clear. I quote this from the compliance Jedi Master @Shawn_Veney:

“If you find your organization manages so many types of CUI, and is perhaps thinking of taking on new work and adding to that challenge; then sometimes it is easier to adopt a high watermark strategy to accomplish your data protection goals. This trade off recognizes that your solution may exceed requirements for a specific type of data; but provides confidence you likely have addressed your aggregate requirements. This is ideal when your internal classification and marking efforts may not be where you would like them yet.”

Throughout this article, I will explain why we have a definitive “Yes” for CUI and CDI in the US Sovereign Cloud. In what will be one of my most hotly contested articles to date, this is intended to spark a debate on how CUI data protection practices apply holistically. I intend to keep this initial argument high level, as there are a million nuances that may be deliberated indefinitely. That said, the “thesis” of this article should be debated passionately as an industry.

At the end of the day, Microsoft offers multiple clouds from Commercial to GCC to GCC High to DoD and even to Azure Government Secret. In other words, we can satisfy many risk profiles and offer you a cloud that best aligns with your organization’s risk posture. We will not police you, nor will we demand you choose one cloud over another. We will be very clear on where we provide contractual obligations. Hence why we are only confident in saying “Yes” to CUI in the US Sovereign Cloud.

Summary

The CUI Program is an ever-evolving initiative to standardize the markings and data protection practices across Federal agencies to facilitate sharing of sensitive information, transcending individual agencies. CUI includes markings that span many categories and groupings. The groupings consist of everything from Financial and Privacy data, all the way up to Export Controlled and Intelligence data. Individual agencies have their own requirements for CUI, resulting in additional rules that govern the data protection practices of CUI. For example, the DoD defines standards in the Cloud Computing (CC) Security Requirements Guide (SRG), in DFARS 7012, and in the Cybersecurity Maturity Model Certification (CMMC) to protect CUI.

CUI is defined by a program that includes all categories under a single umbrella. Not all CUI markings are protected precisely the same way. However, it can be untenable to discern the various restrictions for CUI given consolidated language used by standards and regulations. In addition, the complicated array of markings are often not applied effectively. As a result, the reduced risk data protection strategy is to opt for the highest watermark possible for protection of CUI, rather than risk it by adopting a lower control set. CUI has export-controlled data as a common high watermark, to include ITAR regulated data. ITAR has a data sovereignty requirement.

In other words, CUI effectively requires data sovereignty.

What is Controlled Unclassified Information?

If you have not read the CUI History from the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), I highly recommend it. It’s a short read, and helpful for context.

https://www.archives.gov/cui/cui-history

To summarize, before the advent of CUI, there were a myriad of autonomous Federal agencies and departments that had each developed its own practices for protecting sensitive information. This non-conformity made it extremely difficult to share information with transparency throughout the Federal government and its stakeholders, such as the Defense Industrial Base (DIB).

The CUI program is an ever-evolving initiative to standardize the markings and data protection practices across Federal agencies to facilitate sharing of sensitive information, transcending individual agencies. Ultimately, NARA oversees the CUI Program and is primarily scoped to the Federal executive branch agencies. Major contributors to the program include the DoD, the Department of Energy (DoE), the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), the Department of State (DoS), etc. NARA defines CUI as:

“Controlled Unclassified Information (CUI) is information that requires safeguarding or dissemination controls pursuant to and consistent with applicable law, regulations, and government-wide policies but is not classified under Executive Order 13526 or the Atomic Energy Act, as amended.”

Presidential executive orders evolved to a rule published in 2016 called “32 CFR Part 2002 Controlled Unclassified Information”. You can read about it here in the Federal Register:

https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2016/09/14/2016-21665/controlled-unclassified-information

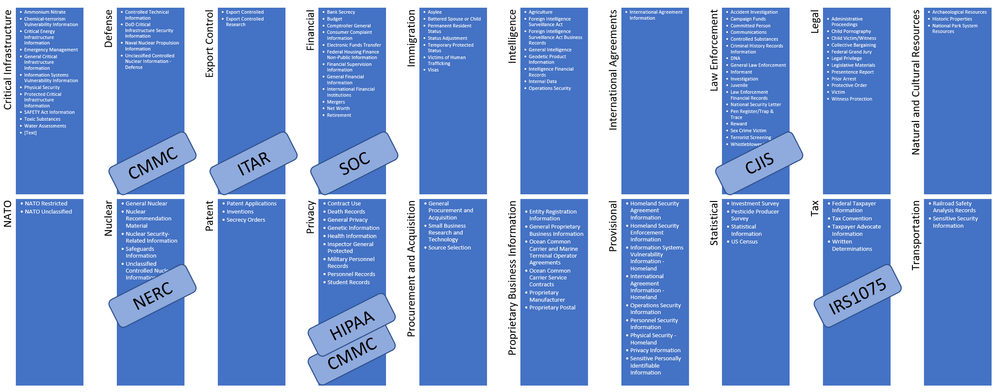

32 CFR Part 2002 prescribes the CUI Program markings that span many categories and groupings. The groupings consist of everything from Financial and Privacy data, all the way up to Export Controlled and Intelligence data. You can find the list here:

https://www.archives.gov/cui/registry/category-marking-list

Illustration 1: Microsoft Summary CUI Registry

Is All CUI the Same?

It goes without saying that each of the Federal executive branch agencies have had their own requirements for CUI, resulting in additional rules that govern the data protection practices of CUI. For example, the DoD defines data protection standards in the DoD CC SRG, DFARS 7012, and in the CMMC to protect CUI. Thus, there does remain a level of autonomy from NARA.

For example, the DoD recently released DOD Instruction 5200.48 establishing policies, responsibilities, and procedures for CUI. It includes a “DOD CUI repository” not accessible by the public. It is intended to address inconsistent definition and marking requirements specific to the DoD expanding what is outlined in 32 CFR Part 2002. The DoD CUI Registry outlines an official list of Indexes and Categories to identify CUI, clarifying what has been a common source of confusion.

In addition, there are multiple regulations that govern specific categories of CUI. For example, export-controlled categories may be regulated by ITAR administered by the Department of State Directorate of Defense Trade Controls (DDTC), or by EAR administered by the Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS).

In other words, while “CUI” is defined by a standardized program of markings and data protection practices, not all CUI is the same. Some CUI categories may generally fall into the bucket of Personally Identifying Information (PII), such as Privacy. Mishandling of other categories may earn you an orange jump suit, such as spilling ITAR regulated data to an unauthorized foreign state actor.

To answer the question, “Is All CUI the Same?” Conclusively No.

Is All CUI Protected the Same Way?

Since all CUI is not the same, certainly not all categories of CUI are protected precisely the same way.

Without going into analysis paralysis on topics such as CUI Basic versus CUI Specified groups, there is a statement that jumped out at me in 32 CFR Part 2002:

“We understand the concerns raised in these comments and agree that the penalties and consequences for failing to adequately protect CUI of some types may differ significantly from failure to protect CUI of other types. That being said, we cannot adjust the definition of CUI to exclude export controlled or other protected information; the Executive Order’s definition of CUI is clear and includes all unclassified information that laws, regulations, and Government-wide policies require to have safeguarding or dissemination controls.”

While we may agree that not all CUI is the same, there is a consensus that all CUI is defined by a program that includes all categories under a single umbrella. So the question is, how do you differentiate between CUI that is sensitive such as Privacy categories, versus those with damaging national security concerns, such as export-controlled data? It’s all CUI, right? Another way to ask the question is, how do you discern the various restrictions for CUI given the complicated array of markings that are not often applied effectively?

Many of you reading this, especially the compliance authorities out there, are thinking “yes, it’s all CUI” but “no, not all CUI is protected the same way”. Technically, you are right. However, I’ve talked to hundreds of organizations out there ranging from the DoD, to the DIB, the FFRDCs (Federally Funded Research and Development Centers), the UARCs (University Affiliated Research Centers), and beyond. I honestly do not hear anyone differentiating categories of CUI for purposes of maintaining compliance with individual markings. When they say “CUI”, they are aggregating all categories together in a comprehensive fashion, not unlike what is described in 32 CFR Part 2002 above. In addition, most recognize CUI markings are not applied consistently and marking efforts may not be where they would like them yet. In other words, they have not located all CUI stored in their enterprise information systems.

Here is another example from the Cybersecurity Maturity Model Certification (CMMC). CMMC defines five Levels:

- Level 1: Safeguard Federal Contract Information (FCI)

- Level 2: Serve as transition step in cybersecurity maturity progression to protect CUI

- Level 3: Protect Controlled Unclassified Information (CUI)

- Levels 4-5: Protect CUI and reduce risk of Advanced Persistent Threads (APTs)

Does anything jump out at you? It’s NOT this:

- Level 3: Protect Controlled Unclassified Information (CUI) of the non-export-controlled categories

- Levels 4-5: Protect CUI including export-controlled categories and reduce risk of Advanced Persistent Threats (APTs)

Why? CMMC Levels 3-5 are intended to protect all CUI. Period. CMMC does not attempt to differentiate CUI that is export-controlled versus CUI that is not. If you delve into the CMMC Model Appendices, you will find many references to CUI, none of which qualify what categories of CUI are in scope per Practice or Process. All categories are in scope for all Practices and Processes in CMMC Levels 3-5. In fact, if you search for “export”, you will find many references, especially in alignment with the NIST SP 800-171.

Assuming you conclude that CMMC is intended to protect CUI regardless of category, you may also conclude export-controlled data, and specifically ITAR data is a common high watermark for compliance.

This article is not about how to become CMMC compliant. This article is specifically focused on CUI. However, there is something to be said about the stated requirements for a CMMC Certified Third-Party Assessor Organization (C3PAO) that uses an external cloud service provider to store, process, or transmit CUI. This is quoted from the CMMC Accreditation Body (CMMC AB) website:

“the C3PAO shall require and ensure that the cloud service provider meets security requirements equivalent to those established by the Government for the Federal Risk and Authorization Management Program (FedRAMP) High baseline and in particular, Impact Level (IL4)”

If the cloud service provider is not DoD CC SRG IL4 authorized, it becomes the responsibility of the C3PAO to provide an independent assessment to address the gaps to become compliant. Most CSPs will not allow ad-hoc third parties to perform assessments on their data centers. Even if they did allow an assessment, it is untenable to make the commercial CSP compliant with FedRAMP and IL4 without significant engineering efforts by the CSP. Trust me, we would not have invested an extraordinary amount to build the US Sovereign Cloud if we could have simply pulled it off in Commercial with a few compensating controls.

The point is, this CMMC AB requirement for FedRAMP High and IL4 to protect CUI does not qualify what categories of CUI are in scope.

Sidebar: The language of requiring an IL4 cloud is nuanced when applied to the DIB and with C3PAOs, as IL4 only applies to Federal information systems. IL4 is not an authorization the DoD will provide to a non-Federal entity, nor is it for a CSP cloud environment not in use directly by the DoD. DFARS 7012 is what applies to non-Federal information systems. I am assuming the intent is to drive the selection of a cloud that has been authorized by the DoD, as opposed to a cloud that is only authorized with FedRAMP. For example, Microsoft Azure Government has a Provisional Authorization for DoD CC SRG IL4, with many services now at IL5.

Speaking of IL4, read this excerpt from DoD CC SRG 3.2.4 Level 4:

“CUI contains a number of categories, including, but not limited to the following: • Export Controlled–Unclassified information concerning items, commodities, technology, software, or other information whose export could reasonably be expected to adversely affect the United States national security and nonproliferation objectives.”

It goes on to define the specific requirements for ITAR. In this case, IL4 is specifically placing an emphasis on CUI to explicitly scope in export-controlled data and how to protect it.

Does All CUI Have a NOFORN Requirement?

Another way to describe data sovereignty, is what may be referred to as “NOFORN”. NOFORN stands for “NO FOReign Nationals”. In other words, NOFORN applies to sensitive data that is not releasable to foreign nationals, governments, nor non-US persons.

I led this article clearly stating not all CUI requires similar handling, such as a NOFORN requirement. However, is it that simple? The above conclusion is that CUI has export-controlled data as a common high watermark of data protection practices, to include ITAR regulated data. ITAR has a NOFORN requirement. Since ITAR is a high bar for compliance, it comes along with a stringent set of requirements for data sovereignty. Using that logic, CUI in aggregate does have an effective NOFORN requirement.

Allow me to pull on that string a bit. I’ve heard a very clear decree that any company certified at a CMMC Level 3 or above, is trusted for data handling of “CUI”. I have not seen any additional qualifications such as “are you CMMC Level 3 *and* ITAR compliant?” It’s implicit the company protects all categories of CUI, including ITAR export-controlled data.

Let’s assume you have two different companies. The first is a company that frequently works with export-controlled data and has a System Security Plan (SSP) in place to protect data with NOFORN requirements. They have deployed their information systems in the Microsoft US Sovereign Cloud with Azure Government and Microsoft 365 GCC High. They have the contractual amendment from Microsoft to support ITAR with NOFORN and have established a clear accreditation boundary for protection of export-controlled data natively within their information systems.

The second company does not handle export-controlled data frequently. They establish an SSP to accommodate protection of export-controlled data using special End-To-End Encryption. They have deployed their information systems in commercial clouds that are not natively compliant for ITAR regulations. However, they pass their CMMC assessment for Level 3 because they have established a human-based process for marking and specially encrypting data before it’s saved to the commercial cloud, relying on people to pre-determine export-controlled data. It’s not a problem for them though, as they rarely deal with it.

Do the two companies have equivalent risk profiles, as they both have certifications for CMMC Level 3? The short answer is definitively no. The second company has a tremendously higher risk of non-compliance and spillage relying on the human factor to protect export-controlled data.

In addition, most export-controlled data does not begin its life as such. Most begin simply as intellectual property, such as documents generated during a research and development project. It’s not until that data progresses through a lifecycle and exchange with the DoD before it gets properly marked as export-controlled (if ever – hello DoD Instruction 5200.48!). If you are saving that data in a commercial cloud unprotected (not opaque to the Cloud Service Provider), you subsequently end up with a deemed export without the fault of the original document author. As such, it is imperative to protect all intellectual property by specially encrypting virtually everything that may potentially become CUI in the future. It goes without saying that is a much easier thing to do if the information systems they use natively support ITAR and NOFORN without the additional End-To-End Encryption applied by the human element.

Here is final example. I’ve talked to many of the DIB with numerous sub-contractors. They do not personally know all their tier 3+ sub-contractors in their supply chain. They rely on a system of checks and balances throughout the tiers to ensure each sub-contractor levels deep is compliant and is obligated to protect their crown jewels. If CMMC is intended to establish a level of trust that any vendor certified at a Level 3 is compliant for data handling of CUI, they should not have to additionally qualify protection of export-controlled data. However, they absolutely do care if the vendor has an accreditation boundary that supports ITAR and NOFORN natively. These DIB may not accept the second company that is in any ole commercial cloud without native compliance. After all, they themselves would not have gone to all the trouble and expense of using the ITAR compliant cloud if it’s not that important.

Conclusion: CUI Effectively Requires Data Sovereignty

Microsoft has prescribed the US Sovereign Cloud with Azure Government and Microsoft 365 GCC High to protect CUI and CDI consistently. Our rationale is that CUI does include ITAR regulated data, and the DoD requires DFARS 7012 to protect it. We only accommodate that contractually across Azure, Office 365, and Dynamics 365 in the US Sovereign Cloud. It’s that simple. It’s true that you may demonstrate compliance for CUI in our Commercial or GCC cloud offerings, but you will not get a contractual obligation from Microsoft to protect an aggregate of CUI anywhere else other than in the US Sovereign Cloud. It will be your sole responsibility to prove and maintain compliance for it in other clouds.

Appendix

Please follow me here and on LinkedIn. You may also find me in forums under the handle wakeCooey.

Here are my additional blog articles:

|

Blog Title |

Aka Link |

|

Accelerating CMMC compliance for Microsoft cloud (in depth review) |

|

|

History of Microsoft Cloud Service Offerings leading to the US Sovereign Cloud for Government |

|

|

Understanding Compliance Between Microsoft 365 Commercial, GCC, GCC-High and DoD Offerings |

|

|

The Microsoft 365 Government (GCC High) Conundrum – DIB Data Enclave vs Going All In |

https://aka.ms/AA6frar |

|

Microsoft US Sovereign Cloud Myth Busters – A Global Address List (GAL) Can Span Multiple Tenants |

|

|

Microsoft US Sovereign Cloud Myth Busters – A Single Domain Should Not Span Multiple Tenants |

|

|

Microsoft US Sovereign Cloud Myth Busters – Active Directory Does Not Require Restructuring |

Recent Comments